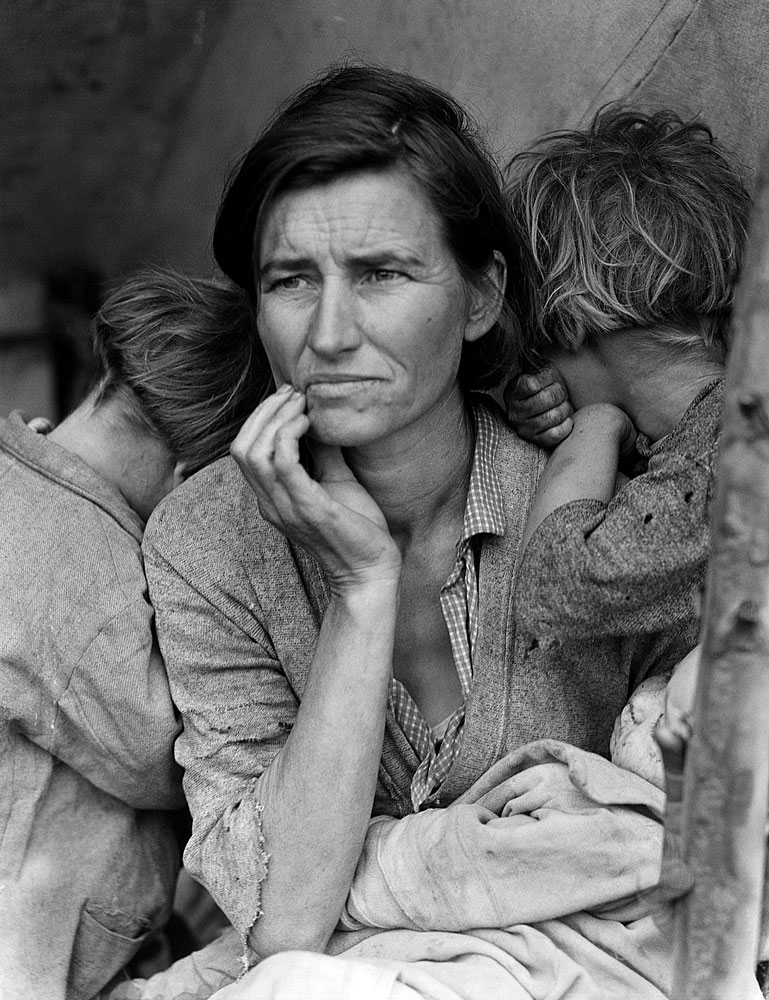

Great Photographs No. 3

Migrant Mother – Dorothea Lange

This iconic image comes from the Great Depression of the 1930s, a time when drought and over-farming had turned vast areas of the US Mid-west into a gigantic dust bowl. Tens of thousands of farmers were forced to leave their lands and take up work as migrant labourers. Many of them travelled westwards, seeking work in California.

Florence Owens Thompson, the central figure in this portrait, was born to Cherokee parents in Oklahoma in 1904. In 1935, already a widow with seven children, she abandoned her dust-choked farm and drove west to California in search of work, picking fruit and vegetables for pitifully small wages.

The exact details of how she came to be at a Nipomo farm when this photograph was taken are contradictory, but it appears that she had travelled there to pick a crop of peas. Unfortunately the crop was destroyed by a freak frost the night before the harvest was due to begin so Thompson was stranded with her children, and a broken down car, virtually penniless.

The life of Dorothea Lange, the photographer, makes a stark contrast. She had trained in photography in New York and, having completed her training in her early 20s, she decided to travel around the world with a girlfriend. They got as far as San Francisco where all their money was stolen.

Lange took up work as a photofinisher and, within a year had set up a successful portrait studio in Berkley. When the Great Depression struck she switched to documentary photography, recording the poverty and hardships all around her. It was a marked change from fashionable portraiture.

At the time of this photograph she was working for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). She had just completed an assignment photographing migrant workers in Los Angeles and was driving back to Berkley in the rain when she passed a sign reading ‘Pea Pickers Camp’. Apparently she drove on for a further twenty miles before making a U-turn and going back. At the camp she found 2’500 cold and starving migrant workers. In her own words …

“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. I made five exposures, working closer and closer from the same direction. I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was thirty-two. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.”

According to Thompson’s son (one of the children in the image), Lange got some details of this story wrong. “There’s no way we sold our tires,” he said, “because we didn’t have any to sell. The only ones we had were on the Hudson and we drove off in them. I don’t believe Dorothea Lange was lying, I just think she had one story mixed up with another. Or she was borrowing to fill in what she didn’t have.”

Lang actually took six pictures with her Graflex 4×5 camera, not five as she states (see the others here). Then she left. “I did not approach the tents and shelters of the other stranded pea-pickers,” she stated. “I knew I had recorded the essence of my assignment.”

To me, this raises the question as to how involved a photographer should be with his/her subjects.

Lange did not ask the woman’s name. She remained unknown for more than forty years. It wasn’t until 1978 that Thompson was identified and tracked down in the Californian town of Modesto by a reporter from a local newspaper.

Thompson is quoted as saying, “I wish she [Lange] hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

It’s true that Lange didn’t sell the photograph. As she was funded by the federal government at the time, the image was in the public domain and Lange never received any royalties. However, the picture and the attention it received gave a big boost to her career.

And the photograph was published. The San Francisco News ran Lange’s six pictures almost immediately, with an assertion that 2,500 to 3,500 migrant workers were starving in Nipomo. As a result, within days, the pea-picker camp received 20,000 pounds of food from the federal government. However, Thompson and her family had moved on by the time the food arrived.

There is no doubt that this image has extraordinary power showing both the strength and the need of a mother in distress. It is truly one of the world’s great photographs.

But should Lange at least have asked her subject’s name? Sent her a copy of the photograph maybe? Even given her a little bit of money to buy some food.

Or must photographers remain detached from the events they are recording, acting as impartial, uninvolved eyes for the rest of the world? Must they keep those eyes clear and unclouded by tears. Clearly, if you are a photojournalist covering a famine, you can’t feed every one of your subjects.

Return to Great Photographs page

What do you think?

(Please note: though your email address is required to control spam, it will not be shown or re-used in any way)

You must be logged in to post a comment.